Oracles: Getting Real World Data onto the Blockchain

Basic Blockchain Use Cases

Blockchain is one of the hottest emerging technology in our world today. Boasting a roughly $300 billion "total market cap" of Cryptocurrency alone, the potential is clearly huge. Smart contracts have come around and exponentially expanded the possibilities for Blockchain technology, for use cases such as:

- Prediction Markets (betting)

- Futures (finance)

- Insurance (claims)

- Contracts (fulfillment)

However, each of these use cases leave one question unanswered. Any distributed application which wants to leverage real world data, such as a betting contract determining which sports team won a game, will need to get that data onto its Blockchain somehow. So, how does that application get that information on-chain in reliable, trusted manner?

Note from the authorslightbulb_outline

This course aims to cover the technical attributes of oracles, as opposed to all specific projects.

However, each of these use cases leave one question unanswered. Any distributed application which wants to leverage real world data, such as a betting contract determining which sports team won a game, will need to get that data onto its Blockchain somehow. So, how does that application get that information on-chain in reliable, trusted manner?

Note from the authorslightbulb_outline

This course aims to cover the technical attributes of oracles, as opposed to all specific projects.

Example: Insurance

Example: Insurance, Scenario 1

Insurance plan via smart contract A covers:

- Illness

- Homicide

- Accidents (e.g. dismemberment) Bob has plan B and loses an arm due to a skiing accident. The hospital rules it an accident and codes everything under covered services. The smart contract automatically accepts the claims as doctors insert a case classification code into their medical records system. In this scenario, the doctors are acting as an oracle by route of the medical records system.

So, the smart contract works as planned.

Example: Insurance, Scenario 2

Insurance plan via smart contract B covers:

- Illness

- Homicide

- Accidents (e.g. dismemberment) Bob has plan A and loses an arm due to a skiing accident. The hospital rules it an accident and codes everything under covered services. His insurance denies the claim, and inputs the denial into their smart contract oracle. In this scenario, the insurance company is acting as an oracle.

Wait - but I thought this was a smart contract? How is it possible for the smart contract to break its programmed code?

In essence, there needs to be a “trigger” for the smart contract to perform actions. Oracles typically serve as those triggers when the smart contract requires real world data. Oracles can be someone with a private key for the smart contract, a webhook, a function call, decentralized voting, hardware plugged into the network, or various other solutions that we will discuss below. Each of these solutions have varying guarantees and attributes.

In essence, there needs to be a “trigger” for the smart contract to perform actions. Oracles typically serve as those triggers when the smart contract requires real world data. Oracles can be someone with a private key for the smart contract, a webhook, a function call, decentralized voting, hardware plugged into the network, or various other solutions that we will discuss below. Each of these solutions have varying guarantees and attributes.

Definition: Oracles

So, what is an oracle?

Is an oracle RNG for bits? A source of data? Trusted authority? Verifiable authority on the state of the world or a certain claim?

The answer is that practically anything that provides you some answer to the question "What is the state of x" is an oracle, for any given x. For example, if you want your smart contract to know what the weather is in Ithaca, New York each day, you could ask someone, check a weather website, call a weather API, or ask a computer hooked up to a thermometer and barometer. All of these solutions are oracles.

“A blockchain oracle is a mechanism that fetches data from the external world to include it in the isolated execution envi ronment of a blockchain. Blockchain oracles are generally off-chain components, so the reliability properties of blockchains do not apply to them. ”

“A blockchain oracle is a mechanism that fetches data from the external world to include it in the isolated execution envi ronment of a blockchain. Blockchain oracles are generally off-chain components, so the reliability properties of blockchains do not apply to them. ”

The bigger question that we have here is: what makes a good oracle? To answer that, we need to define the requirements a bit more.

Why Use Oracles?

Oracles are the backbone of Smart Contracts

Without them, many smart contracts lose their guarantees. To demonstrate that, we offer a real world example of the impact oracles could have.

Here is an example of how blockchain and oracles can be used in supply chain. We start with the ideal timeline of an item being imported to the US. We will see in the second timeline how this is not always realistic, and things like tampering are possible. Finally, we will see how oracles can be used to solve this problem in the 3rd timeline.

Item is farmed

Loaded into international boat

Arrives at distributor warehouse

Item checked in at a drop-off point

Arrives at US Port

Arrives at grocery store and is scanned

Different timelines of an item being imported to the US

Oracles: Example

Online gambling market:

- 56,050,000$ annually

- ~10,000,000 users

- Roughly 1/20 adults will partake in some form of online gambling

- 280% Growth since 2009

This market, with its significant growth and large market cap, has begun to be impacted by Blockchain.

Gambling Data:lightbulb_outline

Statista.comThis market, with its significant growth and large market cap, has begun to be impacted by Blockchain.

Gambling Data:lightbulb_outline

Statista.comIt is typically nearly impossible to reliably determine and verify the results of many things that are used for gambling. For example, a game as simple as blackjack could be rigged in favor of the dealer to the tune of 1% gambling volume per day. With a smart contract, online gambling can be verifiably fair with transparency around any dealer biases present in games.

However, many areas of online gambling are not as simple as blackjack. In sports betting, without an oracle, you cannot determine which team won a game; as a result, sports betting requires some sort of oracle. For a game like the Superbowl, these contracts may begin to yield tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, creating a massive financial incentive for oracles to behave dishonorably, reporting data that would lead to their bets succeeding.

At this point, hopefully it is clear why we need oracles: without them, smart contracts are restricted to use cases that solely involve data that already exists on-chain, such as cryptocurrency. Once we have an oracle, we also need to consider if it is reliable enough for the use case at hand.

Gambling Legality & Blockchain

While traditional online gambling companies are tied to an established legal entity that could be sued in case of illegitimate behavior, smart contracts for gambling can be somewhat anonymous. Additionally, in places where gambling or online gambling may be illegal, gambling on the Blockchain is hard to prevent and prosecute.

Oracle Requirements

Taking into consideration the why smart contracts and Blockchain networks might want to use oracles, here's how we would define these requirements:

- What degree of BFT does the oracle have?

- What would it cost a malicious actor to push faulty data through that oracle?

- What is the ultimate source of the data? (Company? Web feed? Sensors?)

- What is the cost of getting data?

- What is the delay in getting data?

- How secure is the underlying system? Could the oracle system itself be vulnerable?

Oracles: Hardware

Many Blockchain use cases involve some form of hardware oracle. In a supply chain solution, this might be a barcode scanner, camera, or simply an authorized laptop. With these solutions, workers can use hardware to verify which items they handle as they move through the supply chain. However, these oracles by default introduce decreased security guaruntees into the very systems they hope to reinforce. These solutions claim to provide an immutable record documenting and proving the supply chain path of individual goods. However, immutability does not necessarily imply truth: at any of the aforementioned oracles being used to track the goods' movement through the supply chain, information is liable to be faked. For example, a barcode scanner could scan copies of barcodes of items without ever seeing the actual item being verified, falsely providing a supply chain record.

Many Blockchain use cases involve some form of hardware oracle. In a supply chain solution, this might be a barcode scanner, camera, or simply an authorized laptop. With these solutions, workers can use hardware to verify which items they handle as they move through the supply chain. However, these oracles by default introduce decreased security guaruntees into the very systems they hope to reinforce. These solutions claim to provide an immutable record documenting and proving the supply chain path of individual goods. However, immutability does not necessarily imply truth: at any of the aforementioned oracles being used to track the goods' movement through the supply chain, information is liable to be faked. For example, a barcode scanner could scan copies of barcodes of items without ever seeing the actual item being verified, falsely providing a supply chain record.

Oracles: Centralized/Trusted Actors

Oracles can be created in a centralized manner, in which a trusted actor is providing information to be later consumed by decentralized applications. The most well-known example of a centralized oracle is the recently released Coinbase oracle. This oracle is capable of providing real-time price information; however, this introduces a degree of reliance on Coinbase.

As a simple example, a smart contract may intend to offer exchanges between certain Cryptocurrencies. However, without creating an order book, the creators of that smart contract may try to rely on the centralized oracle to determine what prices to offer for exchanges. The owner of the centralized oracle could temporarily manipulate the prices. This manipulation could change the oracle’s price reporting from a true state of 1 Bitcoin to 2 Ethereum, to 10000 Bitcoin to 0.0001 Ethereum, and the malicious actor could then sell an equal amount of Ethereum to the smart contract’s Bitcoin balance.

There are many other, more elaborate examples that could be susceptible to manipulation of a centralized oracle, most notably smart contracts for predictive gambling. Even for a simple Cryptocurrency price oracle, Stablecoins and options come to mind as having potential vulnerabilities when implemented with centralized oracles.

Oracles: Decentralized/Voting

The alternative to centralized oracles is decentralized oracles. Decentralized oracles leverage input from lots of different sources to determine the truths that are reported. This category expands in a few different ways. There are two main types of decentralized oracles, with varying membership policies:

Voting between a number of independent, trusted actors. This could be trusted individuals well-known in the technology community, or it could be large multinational corporations.

Voting within the public.

These types can be further broken down with different solutions:

Hardware devices with sensors that report their information.

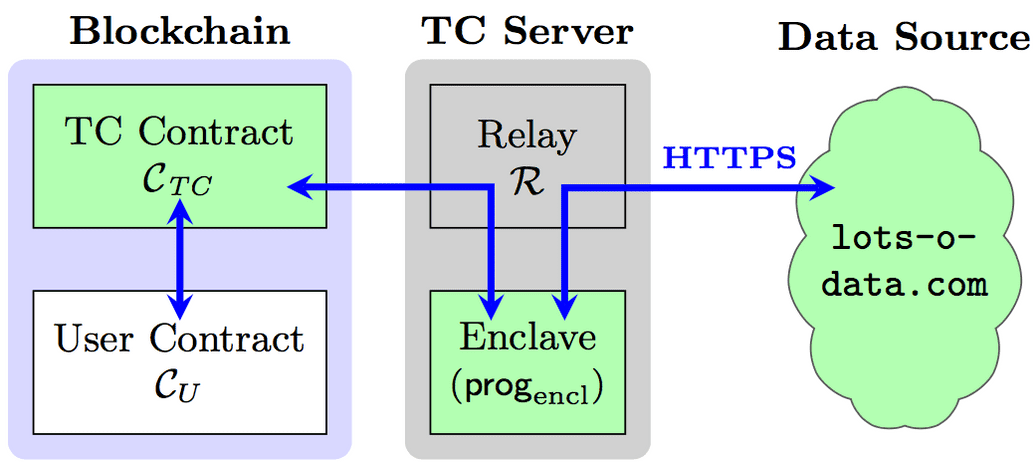

Servers that fetch data from the internet. (Such as Town Crier)

Randomness derived from all the actors contributing to the decentralized system

It is difficult to go into too complete detail here, because there is so much innovation possible in this area. Please refer to the suggested readings to understand how some of these systems might be implemented, and to explore the space more. Oracles involve many complicated topics within consensus, incentives, trust, and security. There are a number of oracles that accomplish some degree of decentralization, but arguably they are still susceptible to manipulation and there is much more improvement to be done.

Suggested Readinglightbulb_outline

Town crier: An authenticated data feed for smart contracts.Astraea: A Decentralized Blockchain Oracle.It is difficult to go into too complete detail here, because there is so much innovation possible in this area. Please refer to the suggested readings to understand how some of these systems might be implemented, and to explore the space more. Oracles involve many complicated topics within consensus, incentives, trust, and security. There are a number of oracles that accomplish some degree of decentralization, but arguably they are still susceptible to manipulation and there is much more improvement to be done.

Suggested Readinglightbulb_outline

Town crier: An authenticated data feed for smart contracts.Astraea: A Decentralized Blockchain Oracle.Oracles: Incentives and Punishments for Decentralized Oracles

In decentralized oracles, there is a question of incentives to consider. In many situations, there may be economic benefit to a majority of the actors to answer untruthfully, or even for additional actors to join the oracle network and answer untruthfully. If thousands of users have interacted with a betting contract, primarily towards the direction of an event with 90% odds of occurring, there might be a million dollars in the contract. Let’s say that there are 99 members in the oracle network: it would only take 100 members to join the oracle network and break the consensus, allowing them to make the oracle report an event that had 1% odds of occurring, and suddenly those 100 people could win the bet regardless of the true outcome of the event, each winning ten thousand dollars.

In order to prevent these situations, decentralized oracles can require members of the system (“Data Sources”) to put up deposits in order to participate in the network. These deposits are used to impart penalties for voting incorrectly, while the system pays out rewards to data sources that vote correctly. This system is susceptible to certain game theory issues, such as if all participants decide that it is most beneficial to collude, regardless of the answer. For example, a data source could simply provide the answer that it sees other data sources providing, as opposed to trying to determine an answer independently (there are feasible solutions to many of these sorts of problems - for the example provided, votes could be secret until the voting period is over).

In order to prevent these situations, decentralized oracles can require members of the system (“Data Sources”) to put up deposits in order to participate in the network. These deposits are used to impart penalties for voting incorrectly, while the system pays out rewards to data sources that vote correctly. This system is susceptible to certain game theory issues, such as if all participants decide that it is most beneficial to collude, regardless of the answer. For example, a data source could simply provide the answer that it sees other data sources providing, as opposed to trying to determine an answer independently (there are feasible solutions to many of these sorts of problems - for the example provided, votes could be secret until the voting period is over).

Oracles: TEE

Zhang et al., from the IC3 (Cornell University), look into using “Trusted Execution Environments” (TEEs) to provide an extra guaruntee to oracles by verifying that the oracle is sourcing its data by running specific code without data manipulation. TEEs, such as Intel's SGX, are enclaves within a computer that are isolated and encrypted through specialized hardware; this allows sensitive data to be partitioned, and is able to significantly reduce the possibility for oracle code to be manipulated. Mast, Chen & Sirer expand upon this design to run databases within TEEs.

Suggested Readinglightbulb_outline

Town crier: An authenticated data feed for smart contracts.Scaling Databases through Trusted Hardware ProxiesZhang et al., from the IC3 (Cornell University), look into using “Trusted Execution Environments” (TEEs) to provide an extra guaruntee to oracles by verifying that the oracle is sourcing its data by running specific code without data manipulation. TEEs, such as Intel's SGX, are enclaves within a computer that are isolated and encrypted through specialized hardware; this allows sensitive data to be partitioned, and is able to significantly reduce the possibility for oracle code to be manipulated. Mast, Chen & Sirer expand upon this design to run databases within TEEs.

Suggested Readinglightbulb_outline

Town crier: An authenticated data feed for smart contracts.Scaling Databases through Trusted Hardware ProxiesRecommended Future Reading

Alexander Egberts has written an incredibly detailed, ~50 page paper explaining oracles in more detail. I strongly recommend reading this paper as a next step to understanding oracles.

Suggested Readinglightbulb_outline

The Oracle Problem - An Analysis of how Blockchain Oracles Undermine the Advantages of Decentralized Ledger SystemsAlexander Egberts has written an incredibly detailed, ~50 page paper explaining oracles in more detail. I strongly recommend reading this paper as a next step to understanding oracles.

Suggested Readinglightbulb_outline

The Oracle Problem - An Analysis of how Blockchain Oracles Undermine the Advantages of Decentralized Ledger SystemsReferences

- Town Crier: An Authenticated Data Feed for Smart Contracts. Zhang et al. (Cornell University)

- An introduction to oracles for asynchronous distributed systems. Mostefaoui et al. (IRISA)

- Statistics on gambling from Statista.com - https://www.statista.com/statistics/270728/market-volume-of-online-gaming-worldwide/

Citations

- Emin Gun Sirer and his course CS6466 at Cornell, in general.

- Linh Vuu, who contributed to the original talk by James Gan which parts of the content from this page was taken from.

Written By

James Gan @https://bellevue.tech

Software Engineer II at PayPal

Rishub Kumar @http://rishub.com

Solutions Engineer at Alchemyapi.io