Hackability of the Blockchain

Can the Blockchain be hacked?

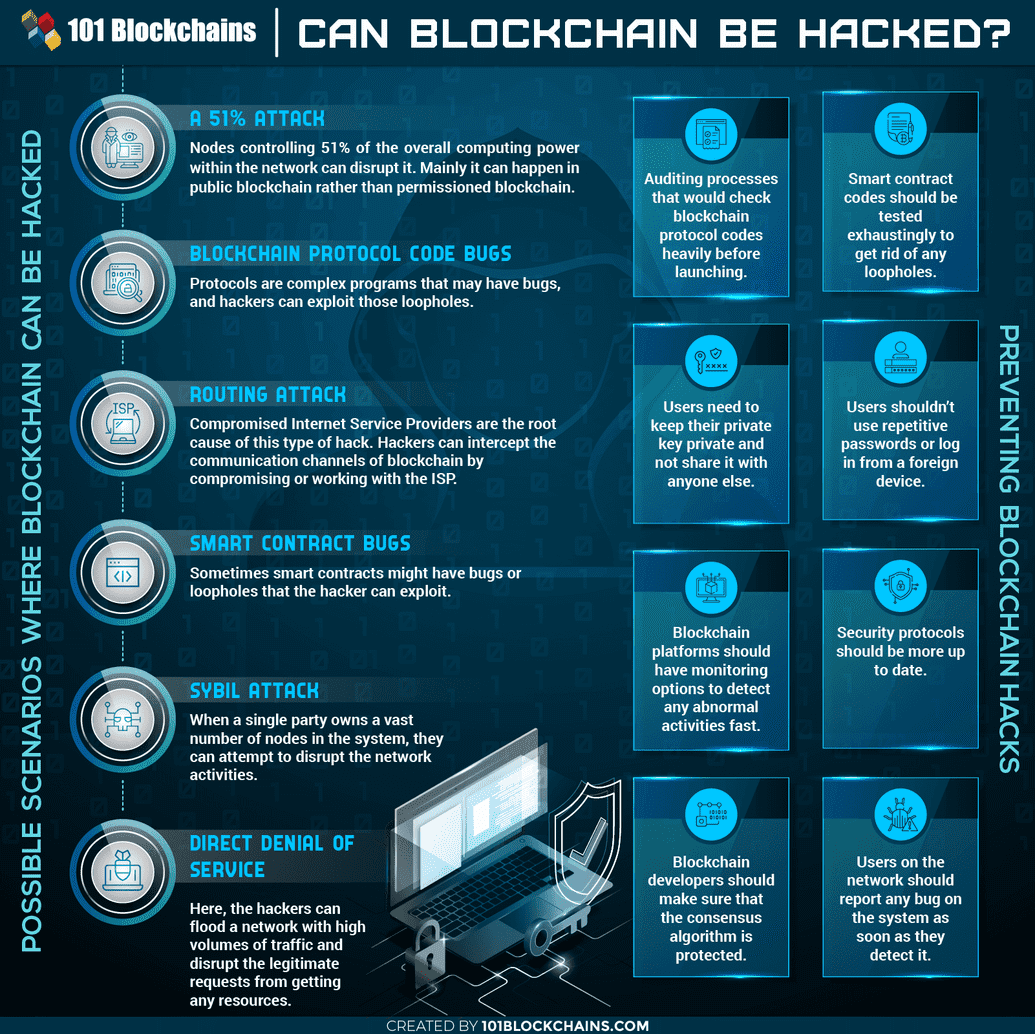

Blockchain is one of the most powerful technologies in the world, and was built around allowing us to control our own data without the need for a central authority. However, like any technology it is not completely perfect, and there are certain ways for it to be hacked, although they can be complicated. Here is a visual with a high level description of the possible attacks/hacks that exist:

We will go over a few of these topics and explain them further.

51% attack

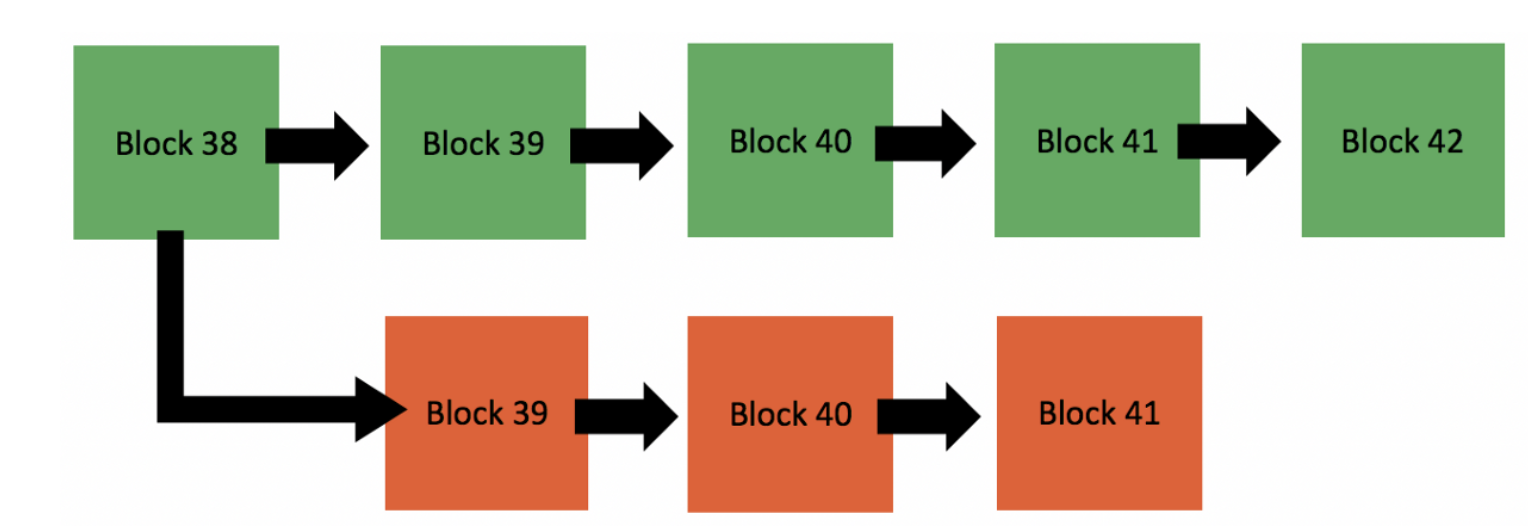

As we have learned, blockchain uses the Proof of Work algorithm to validate and confirm transactions. Nodes perform a set of computations that allow for this, and they can require a lot of computing power. This brings decentralization and the power that blockchain aims to bring, which is no central authority. However, it does require a lot of computing power from nodes around the world that work together to confirm these transactions and ensure the integrity of the blockchain.

The problem arises when one single entity is able to gain 51% of the computational power on the blockchain. This would allow them to manipulate the transaction process and control it as they see fit. If the wrong person were able to get this type of computational power, this would end up compromsing the integrity of the blockchain and cause certain problems like double spend. While this is a risk, it is not serious as bitcoin has required more and more computational power over time, meaning the likelihood of someone being able to hack the blockchain is diminishing over time. Overall, it is still important to understand this phenonemon and know what risks exist.

Step 1: The green blocks represent benign transactions that are being broadcasted to the blockchain by real users. The red transactions are those performed by a hacker attempting to do a 51% attack. Click "Next" on the right for the next step

Smart contract loopholes/bugs

Smart contracts allow for users to create rules and set guidelines that must be followed for transactions on the blockchain. Since smart contracts are immutably deployed on the blockchain, they cannot be altered after being released without a careful rollover plan for its users.

What this means is that any bugs, mistakes, or loopholes that were created in the smart contract remain in the smart contract in a very resilient manner. This means they are free to be exploited, and can result in million dollar losses quite easily. This means writing tests and ensuring the execution of the contract works as expected is crucial. Otherwise, the code could easily allow for malicious actors to gain money they do not own, or even steal money with no real recourse. Clearly, this is a problem and there can be counless bugs that allow hacks on the blockchain.

What this means is that any bugs, mistakes, or loopholes that were created in the smart contract remain in the smart contract in a very resilient manner. This means they are free to be exploited, and can result in million dollar losses quite easily. This means writing tests and ensuring the execution of the contract works as expected is crucial. Otherwise, the code could easily allow for malicious actors to gain money they do not own, or even steal money with no real recourse. Clearly, this is a problem and there can be counless bugs that allow hacks on the blockchain.

Ultimately, due to the nature of programming, there are bound to be bugs and exploits possible at some point. And when these loopholes come up, malicious actors can take advantage of them. These issues are further emphasized due to the nacent nature of blockchain development. There are many security vulnerabilities that arise in smart contracts that might not have been possible, or would have been more easily caught, in a traditional programming paradigm. It is critical for blockchain developers to be aware of these vulnerabilities, stay up to date with them, and regularly audit their code prior to release.

Suggested Reading, Smart Contract Developerslightbulb_outline

Millions of Dollars In Ethereum Are Vulnerable to Hackers Right Now. Pearson, 2018.Decentralized Application Security Project. 2019.Ultimately, due to the nature of programming, there are bound to be bugs and exploits possible at some point. And when these loopholes come up, malicious actors can take advantage of them. These issues are further emphasized due to the nacent nature of blockchain development. There are many security vulnerabilities that arise in smart contracts that might not have been possible, or would have been more easily caught, in a traditional programming paradigm. It is critical for blockchain developers to be aware of these vulnerabilities, stay up to date with them, and regularly audit their code prior to release.

Suggested Reading, Smart Contract Developerslightbulb_outline

Millions of Dollars In Ethereum Are Vulnerable to Hackers Right Now. Pearson, 2018.Decentralized Application Security Project. 2019.Denial of service attacks

Denial of service attacks, or DDOS attacks, are not specific to blockchain and are really common throughout the industry of technology. It essentially requires hackers to flood the network with requests which will make it difficult for actual requests to get through to the systems. While this happens in non-blockchain systems as well, it is very similar on the blockchain.

By sending many transactions to the blockchain to be verified, a hacker could disrupt legitimate transactions from making it through. Due to the computational power and resources required to confirm transactions, this can cause resources to get overwhelemed and thus delay or drop transactions.

While this is not truly hacking, as the hacker as no way of stealing monetary value from others, it can still cause a lot of disruption to the systems and blockchain overall.

Selfish mining

Selfish mining is an additional method of exploiting the blockchain that was first introduced in this 2013 paper written by Cornell researchers Ittay Eyal and Emin Gun Sirer.

The overall idea is that bitcoin assumes that miners will create blocks on the public blockchain. Sirer and Eyal showed that it is possible for miners to hide new blocks and make them available only to their private networks. By hiding these blocks from the public blockchain in a separate fork, they can end up earning more and more bitcoin.

While this is something to be aware of and could end up undermining bitcoin's decentralized nature (Frankfield 2019), there are defense mechanisms against selfish mining as we see in this paper written by a Boston University PHD Candidate.

Further Resource: Automatic Security Auditing Tool

- Paper on Securify, https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.01143

Written By

James Gan @https://bellevue.tech

Software Engineer II at PayPal

Rishub Kumar @http://rishub.com

Solutions Engineer at Alchemyapi.io